Blog – Matt Smith

I am an artist who works mainly with craft-based media, often in relation to collections and archives. My practice often explores marginalised, and particularly LGBTQ+ lives and how they have been included or excluded from museum interpretation.

Previous projects have included Queering the Museum which explored how Birmingham Museum could incorporate queer lives into its displays. Interventions included pairing up historic ceramic bears with a taxidermy otter. When you realise that in gay bars bears are large hairy gay men and otters their slimmer counterparts, then these four objects become a furry gay disco, and the museum a more fun place to be. While this may seem irreverent, I think it sheds light on the role of curators in selecting how objects are combined to tell particular narratives, and how this privileges some people over others.

Closer to Huddersfield, I worked with the Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery at the University of Leeds to explore how oral histories from the Brighton Ourstory Archive could be embedded in everyday objects and paired with paintings in the gallery to move those paintings from the institutional gallery space into the personal and the everyday.

More recently, in Flux: Parian Unpacked at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge which reviewed a large collection of Parianware busts through the lens of colonial atrocities by creating toile wallpapers showing the impact of the British overseas.

I was particularly drawn to working with Memorial Gestures since the effects of the Holocaust were very specific to men who were branded with the pink triangle and arrested under paragraph 175. The persecution of gay men was not particular to the Nazis. Anti-LGBT laws existed before and after the Nazi party but were particularly stringently enforced and extended while they were in power. When the Allies liberated the camps, many men who still had sentences left to serve under paragraph 175 were not liberated but moved directly from camp to prison.

LGBTQ histories are often unrecorded. Fear of persecution meant many individuals would be very careful about being open and in Europe, documentation of queer histories is often centred around medical or criminal records rather than first-person testimonies. Naively, I thought the Holocaust would provide a comprehensive record of men imprisoned under paragraph 175, but the Nazis destroyed many of their records as the Allies advanced, so yet again I was left with a partial and fragmentary history.

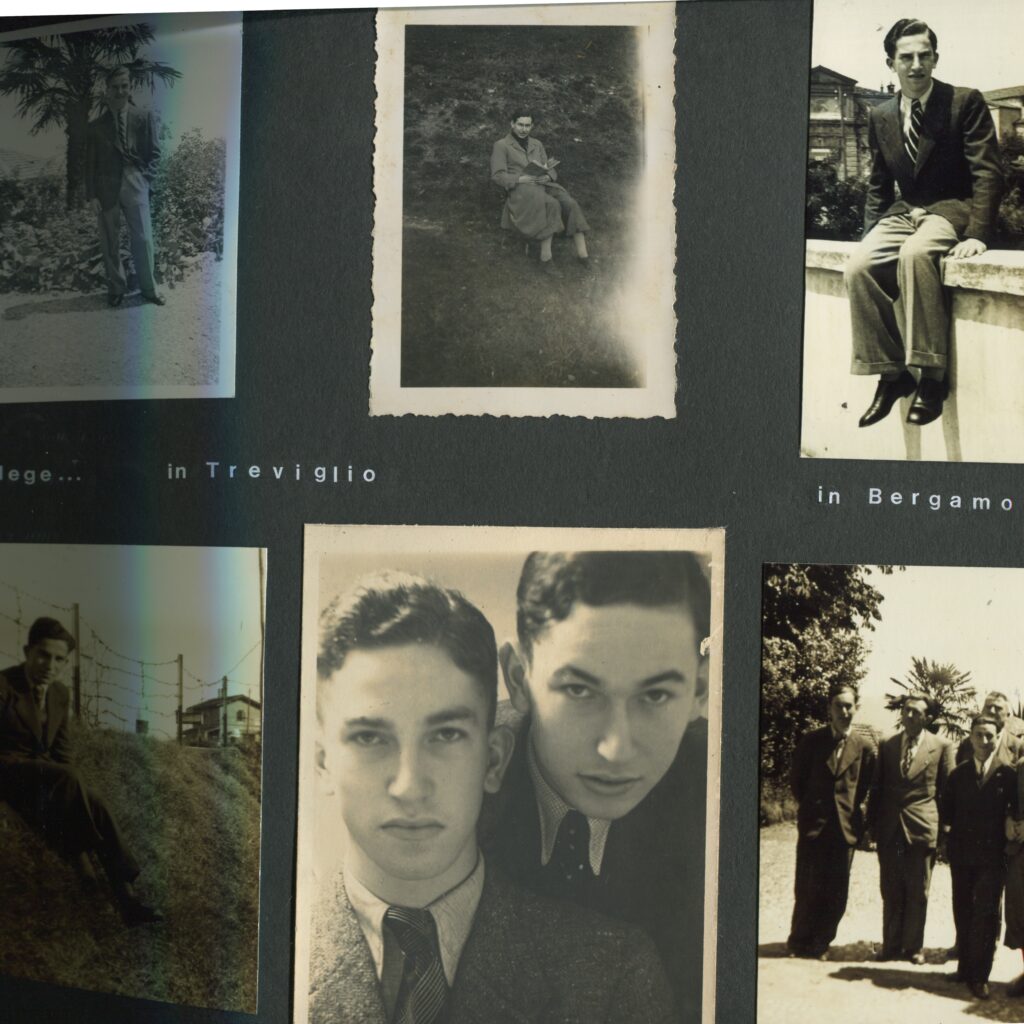

Within the archive at Holocaust Centre North there are, unsurprisingly, very few mentions of LGBTQ lives, and what is there mainly reflects the hostile views towards gay men in the 1940s. Not wanting to perpetuate queer exclusion from the archive, I looked through the archive photographs and chose to let emotion override documented fact: identifying photographs where I felt a connection with the people. Under the Nazis, a touch that lasted too long or suspicion of same-sex desire could be enough to get someone arrested under section 175. I was therefore interested in photographs that showed same-sex sociability or kindness, considering at what point friendship could become the basis for criminal prosecution, and how this might shape how people could show they cared for each other.

Working with the archive, it is clear how much care the archive staff, and the families of the survivors, take to remember and care for the memories of the people whose stories are held in the archive.

For many men, being imprisoned under Paragraph 175 led to ostracization from their families. They therefore never had those family members who would publicly remember them or share their histories with an archive like Holocaust Centre North.

I have no family who were impacted by the Holocaust, but I am part of a group who were. It is a group which traditionally did not communicate history through a vertical family tree: passing memories from parent to child. I contacted the archive at the former Sachsenhausen camp in northeast Germany.

It is estimated that the Sachsenhausen camp housed around 1100 pink triangle prisoners, many of whom worked at Klinkerworks, a huge brick works with notoriously lethal working conditions. The camp has a partial list of the more than 600 gay men who died in the camp between 1936 and 1945. The list tells us almost nothing, but it provides a brief trace of some of these men. I don’t know whether I should feel a connection to these men that I will never know, but I do feel that there is some responsibility to make a space for their memories to be part of the history of the Holocaust.

I hope the work that I produce for Memorial Gestures will somehow placemark these men, and address how their experiences, like so many queer histories, have so often been silent.