I don’t know whether the geography of morality was simpler in the past. Perhaps the compass for most people used to point in a single direction? Today, it can be hard to find the right way to turn, facing a never-ending avalanche of crises, wars and tragedies, amplified by omnipresent news and social media. With current events, you have to make a choice – to take a side, see the nuance, or simply ignore them.

Researching history is often a way to reflect on the present. When you learn about the past, it is almost impossible not to compare and contrast with what is happening in the world right now. This has been a difficult couple of years in my life. A time when I found myself revisiting events like the Holocaust, and contemporary accounts such as Hannah Arendt’s reflections on the banality of evil, in order to be able to process my views about current events and personal tragedies.

That’s why when I saw the open call for a residency at the Holocaust Centre North in summer 2023, I applied the same day. I finally felt ready to unpack this chapter of history, to go beyond the curated perspectives of others in documentaries, books and museums, and to engage directly myself with the raw materials.

I think it is hard for younger people to get their head around this kind of trauma, particularly when it happened on such an overwhelming scale. One of the few silver linings in living through terrible experiences is an opening of the mind to new depths of empathy and understanding. This was what I found when I had a stillbirth last year and had to face the loss of my daughter.

There is an absence of words. An inability or impossibility to adequately express what you feel. Life developed new layers of complexity. It made me realise that behind every account of tragedy, there is more than just the edited storytelling. There is a lot to unpack in the gaps, what goes unsaid and exists in the spaces in between. This is what I want to find by looking into the archives of Holocaust survivors – to hear their voices, not just the lurid or gruesome details, but the way their experience shaped their perspectives, choices and inner emotional lives.

For me and many other Jewish people of my generation– a child of the 1990s– the Holocaust has an unusual place in our lives. We knew the facts. Many of us knew the survivors personally. But the events were distant and removed from our daily experiences. It was like something you keep in a box on a shelf in your living room – too important to store away in a dusty cupboard, but not something you want to unpack and look at all the time.

As someone who was born and grew up in Russia, the war with Ukraine forced me to open this box and take a long, hard look inside it. There are now people I went to school with, sat next to on the bus, passed in the supermarket or on the street, that are actively supporting the killing and destruction. Some may even have committed the atrocities themselves. My nation. My neighbours.

I had always placed myself on the side of victims, which is easy to do when you are a Jew. There was plenty of oppression in my family history and their experiences of antisemitism. But all of a sudden, I had to ask whether I too was a possible perpetrator. Did I do enough to change things and stop the evils that are still happening today? Should I feel any guilt or personal responsibility?

Before I was able to visit the Holocaust Centre North and explore the archives, I decided to look more deeply into my own family history, imagining that I would be able to unearth unknown traumatic stories from my own ancestors. Instead of finding victimhood, I discovered my own great-grandfather was likely involved as a perpetrator, carrying out dreadful deeds ordered by an ideological state. Not the Holocaust, but Stalin’s Great Terror.

Records show that he rose to become a colonel in the NKVD (the domestic counterpart in Russia to the KGB abroad). He had multiple accolades and praise from the Communist Party for his deeds. When I asked, my mother just remembered that he was strict.

This is a pivotal moment when it comes to preserving the memory and the lessons of the Holocaust. The last remaining witnesses to events are leaving us. It was their lives, but what will be left when it only becomes our history?

I have witnessed how quickly history can be distorted, hidden or misused in the wrong hands. In the course of my lifetime, I have seen things change in Russia to ensure that those who researched and helped record the details of Stalin’s mass-murders have become criminalised as foreign agents and members of extremist organisations. It made me realise how brittle or malleable history can be, how crucial it is to properly preserve memories and experiences, to fight the misuse of facts and outright falsification.

With this residency, I feel a sense of purpose. I am playing my own small part in the important task of helping to ensure future generations never forget one of the greatest crimes in history. I am honoured to be a part of it.

Researching the archive has been an unusual and emotional journey for me. A few weeks after I was selected for the residency, I discovered I was pregnant again. I have had to look into how people lost their humanity, while growing a human inside me. I hope for a better future for my daughter, while reading accounts of how quickly an apparently civilised society can fall apart.

For my project, I want to explore the topic of belonging and trust, how people that went through the trauma of the Holocaust could find a new community in a different place in the world. At the same time, I was keen to reflect on the role of small actions and choices, that mean little in the context of great historical events but can be incredibly meaningful in individual lives.

For example, one of the most moving stories I found in the archive was in the correspondence of the warden of the Bradford Hostel for Jewish Refugees, which was host to many children that came to the UK as part of the Kindertransport. One boy, Fritz Terkfeld, had died tragically in an accident. There were dozens of letters over the course of two years, where the warden reached out to multiple organisations – bureaucratic and religious, in the UK and Germany – to try to find out Fritz’s “Jewish name” that was required for Fritz’s headstone and proper memorial prayers.

The archive also provided evidence that children in the Bradford Hostel experienced a highly structured and disciplined environment, typical of the era’s norms. The same warden who took great care in commemorating Fritz might appear stern to the contemporary eye. The boys were encouraged to speak English at all times and had to follow a disciplined routine. And although I realise this approach may have been quite normal at that time, I wonder how this experience impacted the boys.

For the final artwork I am developing as part of this residency, I will be working in clay, which is my primary medium as a sculptor. I have always found that ceramics can be incredibly expressive, both in terms of language and cultural context. Clay has played an important role in civilisation throughout history. Archaeologists and historians can interpret it to understand how people lived, what they held sacred, how they interacted with one another, and even find traces of what they ate and drank. It also preserves some of the earliest records of writing and laws.

This is still very much a work in progress, but I want to create a piece that helps to evoke the same unbearable choices and moral questions and that I have uncovered while studying the archives. Choices and questions that are not entirely absent from our lives today, although perhaps not at the same scale. Alongside this, I want to comment on the disappearance and fragility of evidence and memories, and how we are today witnessing the Holocaust passing beyond living memory.

In the studio, I have been exploring concepts around creating an installation composed of a series of porcelain slabs, that show a gradual progression of breaking and shattering, as if the inevitable consequences from earlier choices.

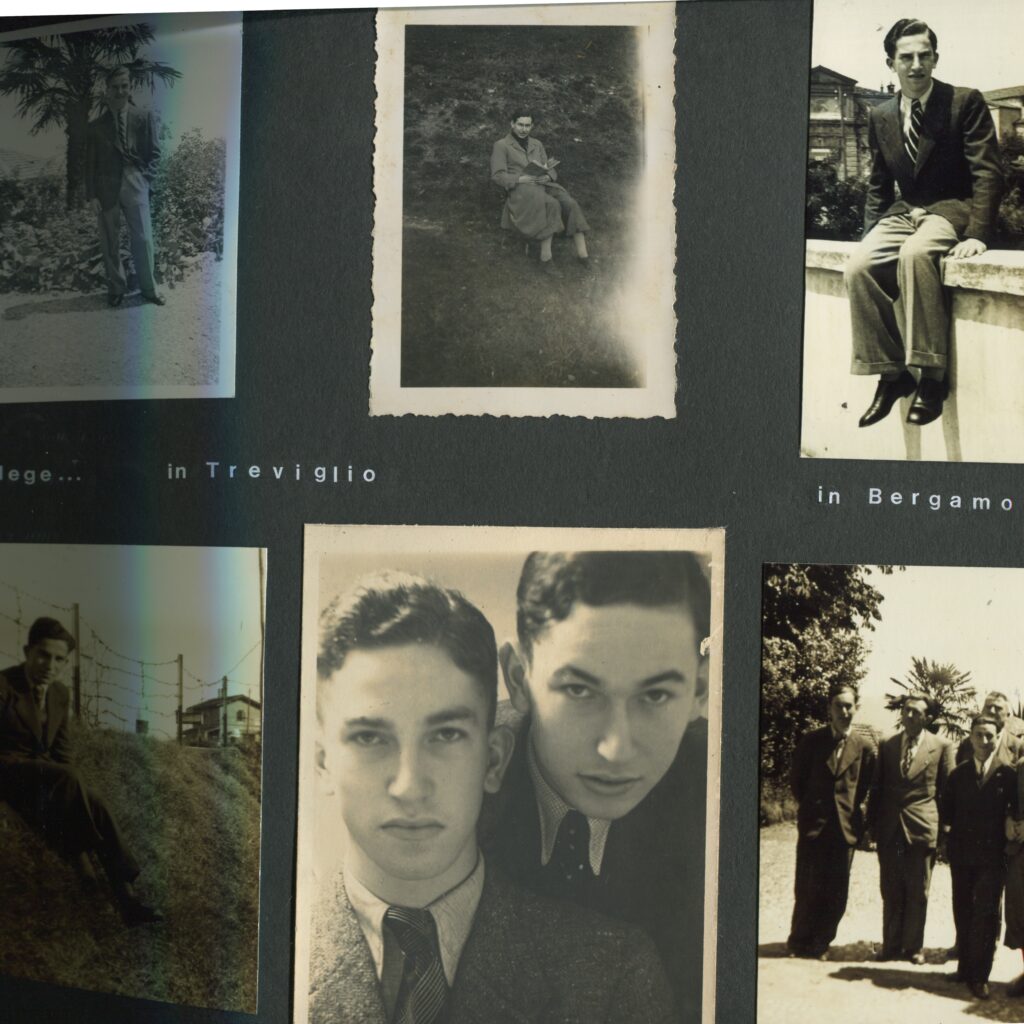

On these slabs, I am intending to use fragments of the letters, photographs, and poetry of one particular survivor, Iby Knill. Iby came from Bratislava to Leeds, via Hungary and after surviving several forced labour camps, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and a death march, facing torture and using her talents as a nurse to help others escape the gas chambers, before eventually marrying a British Army Officer and settling in England.

I am looking at ways to recreate these documents on specially developed ceramic materials that will go through a process of change in the kiln, cracking and deteriorating – crystallising the soft and easily remolded porcelain into a permanent form, but losing details along the way. In this way, we can witness important personal stories, but see how they have become more fragile and precious when they can no longer be changed, and questioning the role each of us has in keeping the memories alive.